I’ve been rereading The Poetics of Gardens, a wonderful, witty, thoughtful book by architect Charles Moore, landscape architect William Turnbull and theorist William J. Mitchell. In two places it references Igor Stravinsky’s Poetics of Music, in which Stravinsky argues that sounds can’t be considered to be music until a human mind has organized them. (John Cage, of course, would argue you blue if you said that to him…) Extending Stravinsky’s argument, Moore and friends argue that a space can’t be considered to be a proper garden until it’s been shaped by human actions.

The situation at the Mojave Phonebooth brings their argument to mind. The Mojave National Preserve purports to set aside a piece of nature for the enjoyment of the general population in a way that mirrors the mission of the Yosemites and Yellowstones of the world. One of the main reasons that we go to these places is to commune with the wonders and pleasures of the world beyond our garden walls and city gates. We go to commune with nature.

But the very names many of these places gives away the real situation, with many of them called “national parks” or “state parks” or “regional parks.” And parks–think of New York’s Central Park–raise expectations of spaces under human control. The removal of the phonebooth was just an obvious symptom of this control, a control that goes througout the natural system, from the construction of roads and visitor facilities to restricting what kinds of activities a person can do in a certain place. Humans are now positioned so that they could exert obvious control anywhere on earth. The Amazon’s getting slashed and burned and there’s comfy year-round housing on the South Pole. And what’ not under control now could be with varying amounts of effort. I’m in some ways a gullible Romantic and I work hard to guard that precious naiveté, but–as much as I hate to admit it–this “nature” thing is now an artificial distinction.

I won’t try to answer the “when did nature end” question, but something’s that interested me is looking at the controls that ended it. It’s been said in various places that one of the methods of controlling something is to name it–Just think of how many mountains bear the names of people that have had political power and abilities to control people and landscapes. A distinct form of naming features is where features in the landscape are given bear names based on their supposed human characteristics.

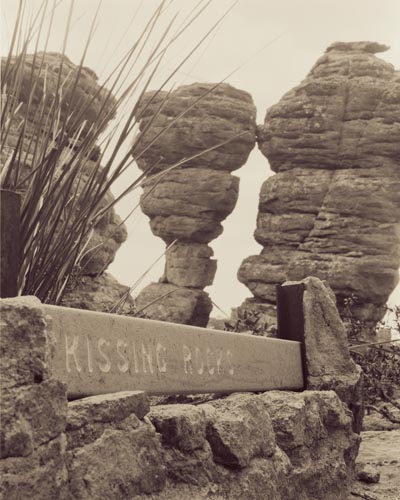

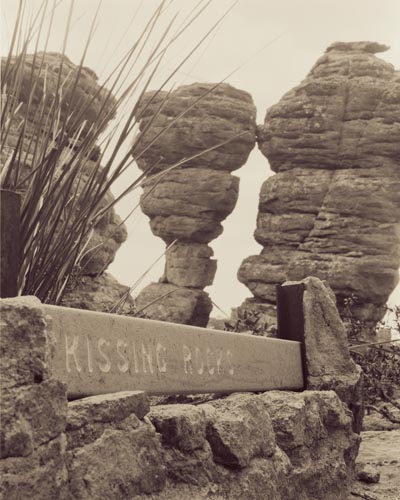

Over the years I’ve been noticing places that have names like “Indian Head” or “Kissing Rocks.” The place that made me really stand up and take notice (and stimulate my gag reflex) was Chiricahua National Monument, in extreme southeastern Arizona, when I first visited it in the early 90s. Here, a 1930s trail goes through an area known as the “Heart of Rocks,” where there’s a concentration of features 10-30 feet tall bearing plaques labeling them in all sorts of distinctly human terms, using names drawn from a hodgepodge of cultural referents. This is where I saw Kissing Rocks, two just-touching formations with lip-like protrusions. Then there’s “Punch and Judy Rock,” and “Totem Pole,” and “Thor’s Hammer.” Mixed in with these, “Big Balanced Rock,” “Camel,” and “Mushroom Rock” seemed much more benign.

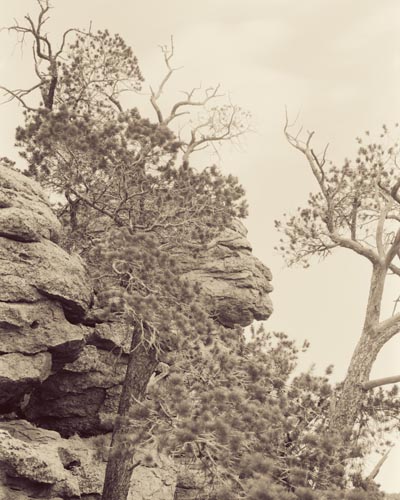

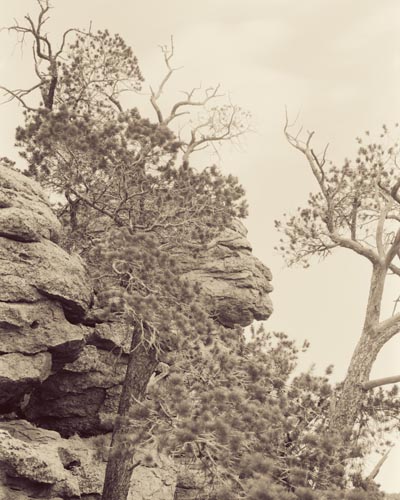

I returned to Chiricahua last Spring and decided that it would be and interesting project to document some of these formations. On the way up the mountain I was explaining what I was doing to a Park Service ranger. Of all the formations, one of the ones that she’d had the most negative reactions to was “Old Maid.” And, down the mountain a ways, be sure to check out “China Boy,” she suggested. Then there’s a whole mountaintop easily viewable from the parking lot at the top of the mountain that’s labeled “Cochise Head,” a questionable homage to Cochise, who held up for several years in these mountains before he was captured.

If you look at the Park Service literature for the park you’ll see “Big Balanced Rock” mentioned, but they’ve downplayed the other names. The plaques remain, however, maybe as a reliquaries to the1930s mindset that came up with most of the names. (The ranger I spoke to thought that Cochise Head might date further back, to the late 1800s.)

So why all these names? Sure, someone was having some fun with it all, but I’m interested in the questions bubbling below the surface. Are humans so scared of or alienated by “nature” that they have to project human traits on it to be able to begin to deal with it? Are we so blind to natural processes and geology that we can only understand it on our terms? Is naming something the beginning of a long chain of controlling actions that ultimately leads to its destruction?

James SOE NYUN: “China Boy,” Chiricahua National Monument, Arizona, 2007

James SOE NYUN: “Cochise Head,” Chiricahua National Monument, Arizona, 2007

James SOE NYUN: “Kissing Rocks,” Chiricahua National Monument, Arizona, 2007

James SOE NYUN: “Old Maid,” Chiricahua National Monument, Arizona, 2007