Sunday was a day of cleaning up the garden to make room for a few new plants. The preferred order of doing things probably would have been to clean up the space and then go shopping, but the big fall plant sale of the San Diego chapter of the California Native Plant Society takes place on one day only, and the Saturday before was the day.

I arrived at the sale with a short shopping list that was arranged alphabetically. The first plants I saw were the two last gallons they had of the first plant on my list, prostrate chamise (Adenostoma fasciculatum ‘Nicolas’). I grabbed the gallons and started down my list. I wasn’t looking forward to doing the rest of my shopping weighed down by twenty pounds of native shrubbery, but there’s nothing like a little physical discomfort to keep you on budget.

The chamise that you usually find in the chaparral is a striking, large shrub with dramatic branch structure. This selection, a form from San Nicolas Island, matures to an open, graceful groundcover, several feet across. When it’s young, like here, it’s easy to mistake it for trailing rosemary.

Chamise has a reputation for being a poor choice for fire-prone locations. Even die hard native plant people who live in wild areas will often actively remove what any plants they find near their home. A conversation I had with one of the experienced local CNPS chapter members made me wonder if its reputation is ill-deserved. His contention was that the plant burns no more intensely that many other natives, and that he’d witnessed a burn line where half of a chamise had burned, while the other half of the plant looked green and healthy. He held that it was yet another case of local fire departments waging war on perfectly good native plants. My plants were going next to a concrete sidewalk along the street, so fire safety wasn’t on my mind. Even if flammable, a low groundcover poses fewer hazards than a big burning bush.

As I continued shopping I ran into one of my coworkers who with the help of his wife was hefting a two-inch pot of the rare San Diego bur-ragweed, Ambrosia chenopodiifolia. The plant can make an attractive little lump, and I was tempted briefly by its rare status. But this species, along with other ragweeds, is considered a severe allergen at PollenLibrary.com, and I have a hard enough time surviving the spring without severe allergens immediately outside.

By the time I checked out I had ten plants, about thirty to forty pounds worth, including a gallon plant of Garrya elliptica and some itty bitty pots of deerweed (Lotus scoparius), yerba buena (Satureja douglasii) and California aster (Corethrogyne filaginifolia, aka Lessingia filanginiflora). And it was at this point I ran into fellow local blogger George from Groksurf’s San Diego. He had a slope, and was thinking about some manzanitas for a slope, some for groundcover, others for larger, contrasting shapes. It had been years since I’d seen him last, so it was a nice chance to touch base and talk plants and water use in the landscape. But I felt bad when I had to excuse myself and get what was feeling like 300 pounds of plants to the car and get back home to finish Saturday’s house projects.

The rest of Saturday would be lots of unpleasant house projects. But I knew that much of Sunday I’d finally be able to get back into the garden. It had been too long.

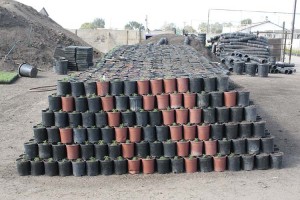

In my little backyard-garden world I’m used to seeing a few plants in pots sitting around, waiting to be planted. To visit such a big facility is to see the world in a different way. Here’s an artfully arranged mountain of gallon pots filled with soil mix being planted with little artemesias. I’ll never complain again about having to pot up a half dozen transplants. Continue reading a visit to recon native plants

In my little backyard-garden world I’m used to seeing a few plants in pots sitting around, waiting to be planted. To visit such a big facility is to see the world in a different way. Here’s an artfully arranged mountain of gallon pots filled with soil mix being planted with little artemesias. I’ll never complain again about having to pot up a half dozen transplants. Continue reading a visit to recon native plants

A plant that was a big hit with many of the bloggers who made it to Chicago for the recent Garden Bloggers Spring Fling was prairie smoke, Geum trifolium. I didn’t make it to Chicago, and I’ve never seen prairie smoke in person. But it looked like I’d have been as struck with it as all the bloggers who witnessed its terrific puffball seedheads in real life.

A plant that was a big hit with many of the bloggers who made it to Chicago for the recent Garden Bloggers Spring Fling was prairie smoke, Geum trifolium. I didn’t make it to Chicago, and I’ve never seen prairie smoke in person. But it looked like I’d have been as struck with it as all the bloggers who witnessed its terrific puffball seedheads in real life.