Ever wonder what your garden would look like if the human caretakers just vanished?

Maybe I’ve been inspired by all the disaster flicks like 2012 or the History Channel’s Life After People series. But envisioning gardens after gardeners is an interesting intellectual exercise that might help us answer that pesky question: What is a garden?

Would all the invasive species take over? Would the native plants reclaim their turf? For how long would you still be able to tell that a garden existed in a spot in the first place?

I looked at parts of my back yard and tried to imagine what would happen.

Within the first month, in Southern California’s dry climate, most of the potted plants would perish for lack of water. Some of the succulents might hang on longer, but without an extensive root system in the ground, they’d be doomed.

This little frog would be staring at a bog garden where all the bog plants have died back, once again for lack of water.

Within two or three months the fishponds would be dry: no waterlilies, no cattails, no sedges, no water for the local birds.

This pathetic patch of grass would go through boom and bust cycles, turning green with the rains, dying back to brown other times of year. Seeds of other plants better adapted to the conditions would eventually take hold. Maybe some plants from the local canyon. Maybe some hardy exotic or invasive species.

Behind the back fence of the house is this slope dominated by rampant iceplant. The the neighbor behind me and I haven’t been able agree on what to do with the space. I’ve planted a small collection of native plants to help stabilize the slope. These are species that with only once exception can be found within a five mile radius of the house, and include plants like this nightshade, Solanum parishii…

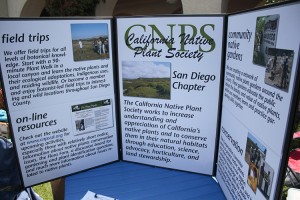

…and Del Mar Manzanita, Arctostaphylos glandulosa ssp. crassifolia, an extremely rare plant that’s on the Federal endangered species list. The neighbor, however, loves their iceplant and can’t imagine of a slope without this gawdawful invasive species clamoring all over it. The local chapter of the California Native Plant Society has prepared a great pamphlet on getting rid of iceplant that you can view [ here ]. It goes into some great reasons to get rid of the stuff:

Planted on hillsides of thousands of homes in San Diego, it has since crawled off the original site and into neighboring Open Space parks, endangering unique plants by smothering them. Iceplant provides little habitat value compared to the plant community that it is replacing. Compared to the native shrubs, iceplant has very shallow roots that do not hold soil well; close inspection often reveals gullies underneath the twisted mat of vines. After rain, Iceplant engorges with water, substantially increasing its weight. As a result, iceplant can cause the deterioration of steep hillsides by encouraging slumping – potentially endangering the house above.

For people in suburbia, “habitat value” might mean plants that harbor scary wild animals and bugs, so that’s not always the most compelling reason to go native. The fact that iceplant might endanger their property values could be more persuasive.

So, returning to my main topic, the iceplant would probably overrun most of the native plants in a very few years and form a deep pile. Once we neglected the slope for a few years and found that the mat of iceplant was starting to push the back fence over. Within ten years the fence would begin to fail and the iceplant would begin its descent into the lower garden.

These plants along the back fence would stand a chance of surviving without water. The yucca, palm, protea would be tall enough to survive an onslaught of marauding iceplant from behind. They’re plants that don’t require much maintenance, and this wall of foliage would probably look unchanged for a number of years. But the lower aloes and other succulents would likely be smothered by the iceplant.

This apricot against the back fence never looks great without summer watering, but it survives. It’s tall enough that it would probably survive the iceplant invasion. Some of the adjacent native plants do great with the natural conditions. They might not cope so well with the marauding iceplant.

The neighbor on the side has Algerian ivy that requires constant clipping to keep it next door. Within two years it would begin to establish itself in the back yard. Taller plants that might survive the iceplant invasion might have ivy crawling up and smothering them.

This raised bed near the house is where veggies and irrigated plants live. Most of the exotic plants wouldn’t make it without water. The Dr. Hurd manzanita, the bougainvillea vine and maybe the Garrya elliptica would probably hang in there, however, maybe for decades, maybe for much longer.

Fifty to seventy-five years out the house would start to fail. Plants might begin to move in. The surrounding garden space would be overgrown with the hardiest drought-adapted species. I almost never plant in rows, but the mixed origins of the species–South Africa, South America, Europe, as well as from all over California, not just local species–would clue an investigator into the fact that a garden existed on the site. The relationships between the plants would be dictated by nature, not a gardener preserving order between plants with mismatched levels of vigor.

Chances are excellent that one hundred years out, maybe two hundred or more, the most persistent invasive species would still be here. Iceplant and ivy, plus fennel and black mustard that have invaded the local canyons, would feature in the neighborhood landscape. But while many invasives bask in the newly disturbed earth of a garden or the re-engineered grades around roads, they don’t always do so well long-term. Biologists have suggested that many native plants would return to a place where they’re not being pulled out or constantly mowed. My yard might be colonized by the local Mexican elderberry, or toyon, or lemonade berry, or prickly pear. And maybe some of the plants I’ve already introduced to the yard will persist and reproduce. The restoration of nature might spread from my house and from the wild edges of nature just a few houses away.

Even after nature returns, the occasional hardy exotic plant surviving amidst the natives, along with some of the neighborhood’s plantings of trees and shrubs in rows will make it obvious: There used to be gardens here.