Gosh, it’s been a while, hasn’t it? The main distractions keeping me away from posting have been a couple of classes I’ve been taking to fill in some art history holes I hadn’t bothered with before. For one of them I’ve been doing a little research on Granada’s Patio de la Acequia, the “Courtyard of the Aqueduct,” one of the gardens at the Generalife, the garden fortress across the canyon from its more famous neighbor, the Alhambra.

This particular garden, a long, rectangular space with a central water feature 162 feet long and 4 across, holds the distinction of being “…the oldest ornamental garden in the Western World, with the additional value of never having ceased to be a garden during the last seven centuries” (Casares-Porcel et al. in Delgado et al., 2007).

I enjoy creative research of this sort, and I thought I’d share some of the cool things that I’ve been finding out.

Today, the garden looks like this:

Peter Lorber. Gartenanlage Generalife, Alhambra, Granada, Spanien eigene Aufnahme, Erstellungsdatum 22.Juni 2006. Photo via Wikimedia.

Peter Lorber. Gartenanlage Generalife, Alhambra, Granada, Spanien eigene Aufnahme, Erstellungsdatum 22.Juni 2006. Photo via Wikimedia.

But like any garden that’s been a while it’s undergone some major changes. The plants, for sure, have gone through a few generations and some major changes. For example, the big splashy bougainvillea that you see behind the column capital on the right side would in no way have been part of the original garden. The Patio was started in the later thirteen century. Bougainvilleas weren’t described until the 1700s, and didn’t make it to Europe until later. And the big splashy fountains are generally bogus to the original as well, having been added in the 1940s or early 1950s by architect Francisco Prieto Moreno. (EDIT: Sep 19: While the fountains are not original, their appearance pre-dates Prieto-Moreno’s work on the garden. I’m still researching when they appeared.)

But the one really mind-blowing discovery that came about in this garden was the result of some excavations done in the wake of a catastrophic fire that consume one of the adjacent structures. Archaeologist Bermudez and his team dug and dug and didn’t encounter the original soil line until they got 70 cm. beneath the level of the original pavement. And his and others’ research began to paint a picture of a garden with planting beds sunken deep between the walkways and water features.

Part of me–the gardener side–says “so what.” Maybe they just dug out the old icky soil and added a new layer on top. But excavations in Seville at the gardens of the Alcázar have found garden beds with stucco decorations on their sides. Others had fresco paintings. So that pretty much convinces me that they weren’t going to all that bother just to bury their ornamental garden bed decorations under a pile of garden soil, and it reveals that these were part of a garden tradition where they had lowered planting beds at least some of the time.

Below is a photo off Flickr of one of those gardens at the Alcázar, the Patio de las Doncellas, the Courtyard of the Maidens, that’s been restored to its original low soil surface. In gardens today you’re used to seeing raised beds, or garden paths near the level of the surrounding plantings. But this? Wow. (There were probably fewer personal injury attorneys around in medieval Spain, so I doubt the ropes at the edges of the garden bed reflect the original way these beds would have been experienced.)

Christophe Porteneuve. [Patio de las Doncellas, Alcázar, Seville]. Photo via Flickr.

Christophe Porteneuve. [Patio de las Doncellas, Alcázar, Seville]. Photo via Flickr.

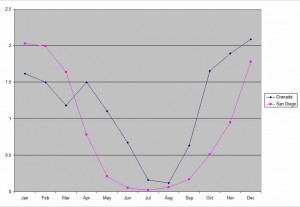

And the last piece of information related to all this was a little graph that I put together trying to see how my local climate stacks up to Granada’s, rainfall-wise. On his most recent visit to lecture at my local California Native Plant Society, Bart O’Brien, author and Director of Special Projects for the Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, pointed out how California’s mediterranean climate is the most extreme of all the five main mediterranean climates in its extremes of wet and dry.

The following compares Granada, located at over 2000 feet of elevation against sea-level San Diego, so this isn’t the fairest of comparisons. And Granada’s annual rain fall is something over 14 inches, versus San Diego’s average of slightly over 10 inches. But you can get a general sense of how extended the California summer dry can get.

Special rights on this post, to comply with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license of the first image:

More Mediterranean than thou by James SOE NYUN is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Based on a work at www.soenyun.com.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://soenyun.com/mailform.html.