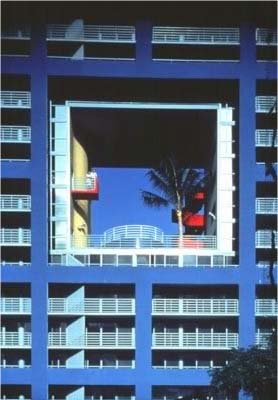

Here’s the latest addition to the garden, a small chunk of the House of Hospitality in Balboa Park, a small chunk of San Diego architectural history.

In the late 1990s the city rehabilitated the building, one of many historic structures built as temporary exhibition spaces for the 1915 Panama-PacificCalifornia Exposition. The exhibit halls weren’t really intended to be a landmarks to pass into time immemorial.  But the city has grown attached to these examples of Churrigueresque architecture, and the buildings are actively preserved.

But the city has grown attached to these examples of Churrigueresque architecture, and the buildings are actively preserved.

(“Churrigueresque” refers to the Spanish/Catalan architect José Benito de Churriguera, who developed a fairly elaborate Rococo style of ornament that was picked up in Colonial Mexico. Bertram Goodhue and Carleton M. Winslow, the architects who worked on the Exposition, studied the style in Mexico and brought it a few miles north of the border. The over-the-top plaster details made for dramatic and escapist exposition buildings, but the details are high maintenance and can begin to fail over the years. It got to the point that the ornamentation was falling off the buildings and threatening to ka-bonk passers-by.)

“Preservation” of the building went through several phases, and eventually employed the wrecking ball. The old House of Hospitality was demolished and a new one erected in its place. To make sure that the new building closely resembled the original the old ornamentation was removed from the buildings and casts made. The new ornamentation is now made of glass-fiber-reinforced-concrete instead of the original horsehair-reinforced plaster.

Rather than landfilling the old architectural ornamentation, the interesting chunks were sold off to benefit the preservation efforts. And it was on a frantic Saturday morning in 1997 where we were able to fight off some of the most aggressive shoppers I’ve ever encountered to pick up this piece of local history. I’m pretty sure that my chunk of history comes from the tower in the photo above, from around the arches.

The fragment was really cool, but it sat in various corners of the house and my studio as we decided what to do with it. Last month we finally decided to liberate the piece back to the outdoors.  Here’s its probably final resting place, attached to a long blank stretch of fence above the fishpond.

Here’s its probably final resting place, attached to a long blank stretch of fence above the fishpond.

I don’t typically go in for lots of garden art or pieces of fake Roman artifacts sprinkled around a garden. But I was happy with how this relatively small chunk of Balboa Park serves as a cool focal point for a part of the garden presided over by a long, plain fence.

In demolishing the original building and dispersing its surfaces the city has managed an odd sort of preservation. Zoos and botanical gardens sometimes have the sad burden of keeping alive species that no longer exist in the wild. And my back yard holds a piece of a building that exists only in a facsimile of the original.