In wildness is the preservation of the world.

—Thoreau

In a desert, golf is the utter ruin of the known universe.

—Me

This is the week of the U.S. Open golf tournament here in San Diego. Something like 42,500 spectator tickets per day have been sold for three days of practice rounds and four of competition. It’s being described as having a string of Super Bowls hitting town, seven days in a row.

To mitigate the potentials for traffic headaches they’re running shuttles for the spectators from Qualcomm Stadium, where they last played the city’s last real Super Bowl, up to the Torrey Pines golf facility, located on the brink of a cliff four hundred feet above the broad sands of Black’s Beach, one of the most spectacular clothing-optional beaches remaining anywhere. And yes, in addition to being a spectacular location for a nude beach it’s also a stunning place to plant a golf course.

The Torrey Pines golf course [ source ]

In addition to the shuttles, they’re asking employers surrounding the golf course to limit how many employees show up at work this week. Beyond that, some of the office buildings that border the golf course effectively have been ordered shut down. Rumor is that they don’t want non-paying working stiffs to get a free look at Tiger or Phil or Adam, and that there are security concerns.

To add to the chaos, add to everything that this is finals week at the University of California, located just across the street from the golf course. Oops.

All that rubs me the wrong way. While it might be appropriate to maintain golf courses in cool, wet places like Scotland, it seems somewhere between bizarre and socially irresponsible to dedicate thousands of acres to the game of golf in the desert that is Southern California.

Water is at the forefront of many a Californian’s thinking. Many of us plant our gardens with drought-tolerant plants to maximize our water usage, and we try to limit the size of our lawns.

The San Diego County desert town of Borrego Springs grew to some size as an agricultural area, then began to attract people who grew the town even further. With those people came golf courses and the kind of water use that goes with them. The numbers aren’t exact, but of the total water intake of the town, something like ten percent goes to households (including landscaping), while twenty percent goes to golf courses. The rest goes to the farmers who are complaining that their aquifer is being drained dry. The proportion of water use between residences and golf courses is similar in other desert areas like Palm Springs. So, in a desert, huge numbers of golf courses don’t make much sense.

In addition to the water issues, golf courses are profligate users of pesticides and herbicides. After all, who wants to play golf on a course with brown spots? The Beyond Pesticides site posted a piece establishing links between golf course chemical use and various cancers, and Golf Digest of all publications ran an article, “How Green is Golf,” in its recent May 2008 issue looking at the issue.

Their conclusion? “New courses in the desert will become rarer,” and “The residue of synthetic chemicals are found in high concentrations as far away as the Arctic,” and this quote from a participant at a symposium at Pebble Beach: “From what I know about Augusta National, it’s really a television studio and not a golf course.”

There are signs of encouragement. The weekend San Diego Union-Tribune had an article on how master-planned golf communities are on the wane here in town. Much of the reasoning is economic. There were days when you could build a course here for a million dollars a hole, but rising land values have made that impossible. Seems that the majority of the people who bought into a golf community valued the perceived open space, but only a minority of them ever played the game. It’s proven to be cheaper to set down some hiking trails and preserve the natural open space. In addition, with what is known now about the health hazards of living on a golf course, who’d want to pay extra for the privilege?

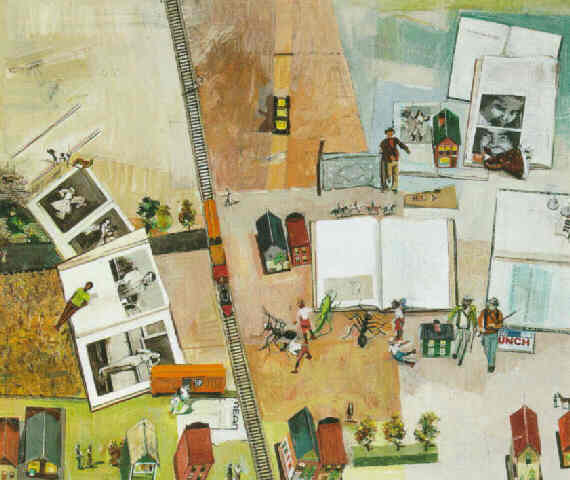

So this week I get to endure the U.S. Open along with much of San Diego. While I’m doing that, I keep flashing to this picture in my mind of a driving range that I saw on the outskirts of Borrego Springs, probably the most socially responsible golf facility that I’ve seen anywhere. (Next time I’m out there I’ll try to snap a photo of it.) What tells you it’s a driving range isn’t the sickly fake-green color of its grass. In fact, nobody waters it, and the range is the color of the surrounding desert.

Instead, what tips its hand as a driving range are the golf balls scattered over the facility: thousands of the little white things, glistening in the vibrating mirage-inducing midday atmosphere like bright desert rocks arrayed over the pale brown sands. Now that’s my vision of paradise!