People often try to do the right thing, but along the way things somethings can go astray.

Saturday I was hiking one of our local urban canyons, San Clemente Canyon, with some other plant people. Like the rest of our local canyons, the plants you find there are a mix of native and introduced species. It’s not pristine, by any means, particularly when you consider that there’s a freeway a couple hundred feet behind where this photo was taken. But many of the really big plants are original to the canyon. You can get a good impression of what it was like two centuries ago, and hopefully that’ll motivate people to preserve what’s left.

During that walk everyone paused at a big clearing in the trees. It was a broad area that had been cleared of the invasive species and replanted with California plants. The project was financed by the city authority that maintains the sewer lines that run through the park. The maintenance roads eat into the native habitat, and for ever acre of road, the agency did an offset of five acres where they tried to mitigate the damage done by the bulldozed access routes. It’s a pretty reasonable way to deal with something a big city needs to operate–sewers–and at the same time improve the integrity of the semi-wild spaces.

After oohing and awing at the improvements, several of us noticed the poppies. California poppies, yes they were, but big, tall orange ones and not the petite yellow-to-gold ones that you typically find in the local environment.

A trip yesterday to Tecolote Canyon, another of the local urban canyons, revealed exactly the same thing in a restoration in progress there.

Technically, under current botanical systems, both versions of the poppy are considered the same species. But a quick look at them yells you that they’re as distinct from one another as cousins in a family, and they have genetics that evolved to making them appropriate for their different environments.

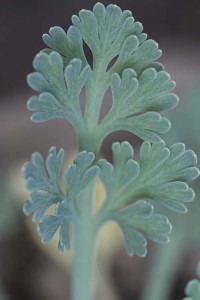

Take a look at their leaves, to start. The one on the left, below, is from the classic “California poppy” that people know (Escholzia californica). The one on the right is from the version found around here (at once classified as Escholzia californica maritima). The one on the left has less leaf surface, and to me looks like it’s evolved to deal with more drought.

Growing the two versions side-by side in the garden also reveals another difference. The regular California poppy develops powdery mildew this cool and humid time of year, whereas the local version seems to be close to unaffected.

So when you combine the plant size, flower size, flower color and the plants’ resistance to powdery mildew, you can see that the plants are quite different, and that the coastal version is probably better suited for living here. (In gardens the typical orange form is pretty rugged and no slouch, but its disease issues give it a disadvantage to being as spectacular as it might be in a drier region like the Antelpe Valley, the location of the California Poppy Preserve.)

Recon Native Plants, a San Diego wholesale native plant nursery that specializes in habitat restoration, takes extra pride in knowing exactly where their plants come from. Their site advertizes:

For example, an Artemisia californica from the Sierra Nevada and an Artemisia californica from coastal San Diego County are the same species, however they have evolved and adapted with different genetics for different environments. With the source identified, RECON Native Plants can tell our clients within 5 miles, the origin of each plant and the client can select the location most appropriate to their project.

It’s a good illustration of the difference between planting a garden and going the extra distance to effect a successful habitat restoration project. Many gardeners would prefer the splashier Antelope Valley version of the state flower, but that’s not the form that makes most sense for our local flora. Somewhere along the planning, implementation or sourcing of these two habitat restoration projects, something went a little astray. It’s a small detail, but it’s one that many people consider important as we try to keep our open spaces as wild as we can.

EDIT, April 7: Check out another post on two different poppy forms over at DryStoneGarden.