One of the things I like to do in art museums is to look at the fruits, flowers and vegetables in still life paintings from a couple or more centuries back. Often I recognize exactly what the plant life is, but other times I see things that look like no plants I’ve seen or food I’ve eaten.

When I was cleaning off my desk at work the other day I ran across an exhibition brochure of Spanish still lifes that one of my coworkers had picked up on her last trip to Barcelona. The show featured work by the like of Goya, Zurabán, and Juan Fernández “El Labrador.” The painting in the brochure that caught my eye was by Jaun Sánchez Cotán, a painter who created one of my favorite series of still life works.

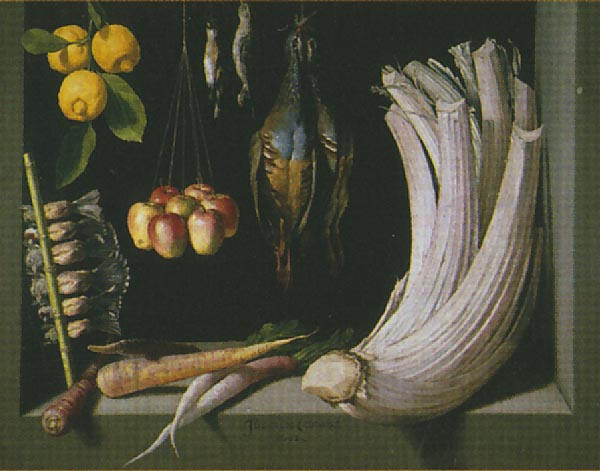

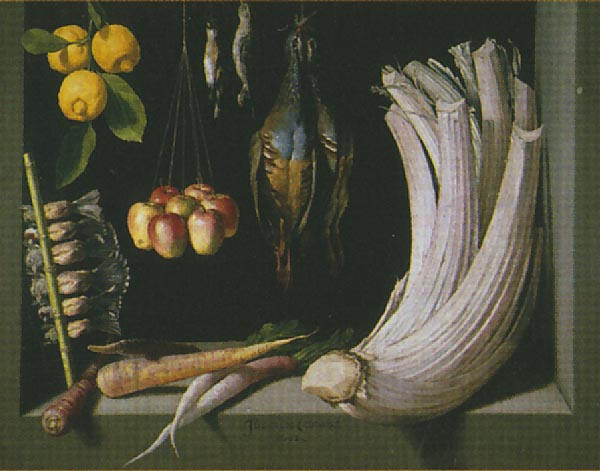

Jaun Sánchez Cotán. Still Life of Game, Vegetables, and Fuit, 1602. Oil on canvas. Prado Museum.

In the painting, in addition to the game, there are lemons and apples that look absolutely recognizable, like what you’d find at a farmer’s market today, though the apples–a beautiful gold with a rosy-red blush–look smaller than the modern hybrids today. The root vegetables look like parsnips, and something else a bit whiter, like today’s daikon radishes. But I doubt daikon would have been a hot seller in 1600s Spain.

The stick to the left with stuff attached to it–What are those? Squab? I can’t make it out clearly in a little two-by-three-inch brochure reproduction. But it’s the massive, gracefully curved veggie to the right that dominates the painting and steals the show. It’s to my eyes a cardoon, an edible thistle very similar to artichokes, though not a variety you see in stores much these days.

There’s a good description of cardoon in the Anioleka Vegetable Seeds Co. listing:

For culinary use, unlike the artichoke where the flower heads are eaten, with Cardoon, it is the thick leaf bases, hearts and roots which are utilized for food and harvested in the early spring to early summer months. Cardoon can be used in soups, stews and salads and has a slightly spicy, celery-like flavor similiar to Artichoke hearts.

Much of Cardoon’s lack of popularity is due to the fact that like the artichoke, a tremendous amount of space is required to grow them. Cardoon can grow up to 7 feet in height and is very evasive [i.e., invasive] in most climates. Care should be taken to remove the flower heads of the plant before they produce seeds, for Cardoon can agressively naturalize throughout your property.

In addition to naturalizing throughout your property, this plant can take do lots of damage to your local ecosystem. You run across large stands of artichoke thistle in the local Southern California canyons, and I wouldn’t be surprised if they were actually cardoons loosed from gardens or agriculture. Go ahead and grow them, but grow them responsibly.

But back to the Sánchez Cotán painting. All the beautifully rendered fruits and veggies and game occupy this dramatic space that looks something like a black cupboard or windowsill, but also something that looks like a dark infinite void. Because of this amazing space and ambiguity it looks decidedly modern and fresh to my eyes. And the vibration back and forth of the once-live subjects with the dark dark darkness conjures up notions of life and death, and the fragility of existence–all that without the cheap theatrics of skulls that often appear in paintings like this. This is vanitas painting at its best.

The painter uses this background in several other works, including my absolute favorite one of the series, a painting that so happens to be in the collection of my local art museum:

Jaun Sánchez Cotán. Quince, Cabbage, Melon and Cucumber, 1602. Oil on canvas. San Diego Museum of Art.

I can’t tell you how much I love this painting. A good forty percent of the surface is black. Absolute, utter black. The fruits and vegetables begin in the light, and draw your eye as you follow along the graceful curve from the lively quince, to the extravagantly ruffled cabbage, to the sensual melon sliced open with a slice taken out for you to savor with your eyes, and finally to the final vegetable, a cucumber that curves gently but insistently towards the back, towards the enveloping blackness, a blackness that makes itself felt every bit as much as any of the fruits and vegetables.

Quinces and cabbages today look pretty much like what’s in the painting. There are so many melons out there that it’s hard to keep track, but it looks like an ancestor to the French heirloom sold today as Charentais. And the green, lumpy cucumber–It’s totally recognizable, though it looks closer to gherkins or the Asian varieties than the smooth, plastic-surfaced cukes that you see in the stores most of the time.

Interesting vegetables, for sure, and what an amazing painting!