I now have a new appreciation for the work of field botanists.

A couple weekends ago I had a chance to work on a rare plant survey on the slopes of Viejas Mountain in eastern San Diego County. I enjoy seeing plants out in their wild habitat and the description of the task sounded downright idyllic: You go out to trailless edges of the county, enjoy the scenery, and all the while look for rare plants.

The plant of special interest for this trip was San Diego thornmint, Acanthomintha ilicifolia, a plant found only in a smattering of places in California and bits of northern Baja. And the plant is even more selective than that. It only grows on clay lenses–gently or moderately sloped areas of clay soil that has washed down from nearby areas. The surrounding chaparral plants for the most part don’t care for these soil conditions, so they create openings for this rare annual to colonize.

The project was to get a population count of thornmint from areas where they’d been sighted more than a decade earlier. Comparing today’s numbers against the earlier censuses would give you an idea of how well the plant is doing in the wilds.

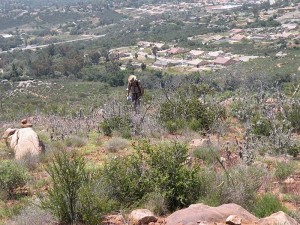

Our assignment was population 51, a cluster of adjacent stands on the western edge of Cleveland National Forest, just outside the city of Alpine. (Looking back on the suburban sprawl I thought it looked a little like the photos of Area 51 taken from Freedom Ridge.)

Most of the spread had burned in one of the recent major wildfires to go through the county and was in the state of growing back—pretty successfully, since travel got to be tough some of the day. Whenever the chaparral parted and the soil conditions looked right, you scoured the ground for thornmints, which at this point in their lifecycle were mostly 1-4 inches tall, with most of them not yet in bloom.

One of the three sub-populations we looked at was completely gone. Nada. Zero plants. Maybe the fire wiped them out. Maybe we weren’t observant enough, though we fine-tooth combed the hillside.

But the other two populations gave us an exercise in counting plants. Lots and lots of plants. Tiny, tiny little plants.

By the middle of the afternoon we had a count, 21,015 plants. It was six hours of open slopes with no shade spent in deep concentration looking for the little plants, counting all the while.

I’ll confess: We did a little estimating when the populations got really large, and so we didn’t actually physically count all 21,015 plants. But 21,015 seemed like a solid estimate.

While it’s good to know that there are more than a handful of plants left in the wild, it’s also a little unnerving to see that they have such a limited distribution, and more disturbing that one of the three populations from earlier seemed to have vanished.

Locally common, but in the grand scheme of things, awfully rare, especially with human encroachment from Area 51 next door.

San Diego thornmint probably won’t turn into one of the great garden plants for California native gardens. But along the way we saw plenty of species closely related to those used in home native landscapes: laurel sumac (Malosma laurina), ceanothus (tomentosus and foliosus), stinging lupine (Lupinus hirsutisimmus), manzanita (one of the Arctostaphylos glandulosa subspecies)…

…and one of my favorite flowering natives: blue-eyed grass, growing and blooming among the tiny little thornmints.

Usually my camera is the first thing I pack for one of these outings, but somehow I forgot it at home this time. My thanks to team-leader Janet for the use of her images from the trip!