Are gardeners terrorists? You’d think so looking at the sign posted outside the San Diego County Fair.

This gardener took advantage of the “Furlough Friday” deal for state employees (free admission!) and checked out the offerings of the fair for the first time in half a decade. I guess the rationale of free admission was to get more people in the gate to partake of the rides and stunt food–you know, the bizarre offerings that often involve impaling something on a stick, sticking it in batter, and then deep-frying it. I searched all over for the worst of the worst stunt food but the best (worst?) I could find was a stand offering “fried Twinkie lattes”–really nothing more weird than a vanilla latte–and this trailer selling chocolate covered bacon. Neither dish really seemed to be deep fried, so I guess they’re getting with the health-conscious kick…

My main destination was the outdoor garden displays, where the main point of each display seemed to be either attracting new customers to the landscape firms there or–in the case of the non-profit institutions and garden clubs–education. The fair’s never been about landscape design as a high art, but there’s always interesting stuff there.

If there was theme to the displays this year, “edibles” seemed to be the word, keeping up the health-conscious theme of the not-deep-fried chocolate-covered bacon. This display by the San Diego Botanic Garden in Cooperation with the San Diego Water Authority won the prize for the best edible landscape. The display also won an award for the exhibit that arranged plants in a way that demonstrated “good taste.”

It featured food crops and ornamentals of all sorts as long as they fit into the purple-pink-green-silver palette, and demonstrated that a garden with veggies could be as pulled together as any other garden. In its combination of cool-weather crops (such as purple cabbage) with warm-weather ones (like basil and squash) it was also a reminder that this is a garden show than a real-world garden.

Here are a few more photos of displays that played with the edibles theme:

I kept my eye out for uses of native plants, but there were almost none. Part of that is probably because the majority of the charismatic flowering natives do their thing at the end of winter or during spring. The one main exception was a small display by native plant specialist Tree of Life Nursery.

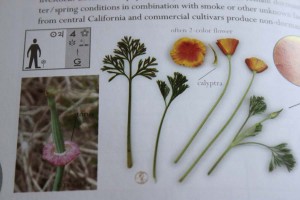

Inside, in the adjacent exhibits building, there was a flower show going on, with roses and dahlias and gladiolus and lots of cubbies with flower arrangements. And that’s where I saw a few more natives, where they had a category for cut native flowers. So there was more monkeyflower here, along with one of the bush poppies (Dendromecon) and some matilija poppies.

Really, who doesn’t love these matilijas? The last photo is of one of them. Next post I’ll share some other sightings.

As such it’d be a good writeup of species I’m using to seeing in my area seen through the filter of someone working in the Los Angeles/Orange/Riverside County region of Southern California.

As such it’d be a good writeup of species I’m using to seeing in my area seen through the filter of someone working in the Los Angeles/Orange/Riverside County region of Southern California.