Desert Center, California lies about halfway between Indio and the Colorado River, halfway between a hot, flat desert town and the Arizona border. Unless you need to stop for gas, you pass by it on I-10 at wide-open highway speeds. It’d be a blur like any other anonymous desert town if it weren’t for the palm trees.

The huge date palms there grow single-file in formations that describe wide circles, V-shapes, or a triangle that’s many acres across. Transplanted there by Stanley Ragsdale in the early 1990s, most of the trees now have seen better days. Even for drought-tolerant date palms, irrigation is essential here in the low desert. The watering proved inadequate and many of them died. In their current state of falling into ruins the trees are visually amazing, the vegetable equivalent of the Acropolis.

James SOE NYUN: Palms I, Desert Center, California

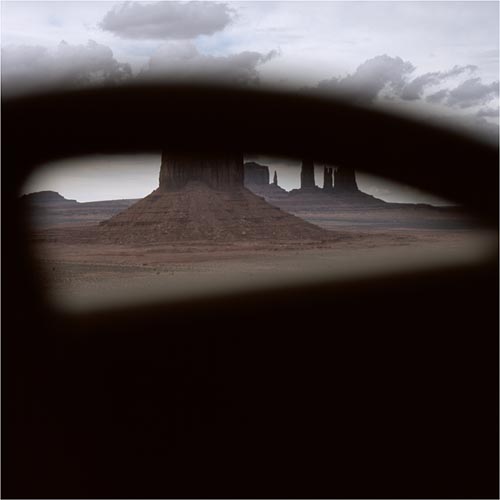

I first went to photograph the town and its trees in 2003 on a hot, breezy day in April. It was approaching noon, and there was no shade other than what a minimal palm trunk could provide. It’s not the sort of lighting situation that a lot of photographers consider acceptable, but for this body of work it was perfect. Besides, so many of the well-known 19th century expeditionary photographs of the American West were taken in harsh conditions similar to what I encountered. Palms I, above, and Palms II, below form a diptych: Imagine Palms I on the left and Palms II on the right.

James SOE NYUN: Palms II, Desert Center, California

There weren’t many structures there next to the interstate, not much beyond the obligatory cafe and gas station. The big surprise, though, was an abandoned school, compact, constructed of brick, and modern in its architecture. It had almost no windows in the classrooms except for high clerestories place beneath broad, sheltering eaves. Not that different from the schools I attended up in the Los Angeles area, I thought. In photography–and in painting for centuries before it–ruins are often a bit of a cliche, but name me a landscape photographer who hasn’t shot some at some point. I couldn’t resist:

James SOE NYUN: Breezeway, Abandoned School, Desert Center, California

Both the palm trees and the town clearly had seen better days. Stephen A. Ragsdale, the man who founded the town in 1921, died in 1971. Stanley Ragsdale, the one who directed the planting of the trees, died in 1999. Without their energies, this area of the city faltered, and the palms began to fail. The town and these landscapes shot there function for me like Northern European vanitas paintings, reminders of life’s struggles, its shortness, and the certainty of entropy. Again, those aren’t transcendentally fresh ideas, but to see them particularized in a place that’s struggling though still very much alive fascinates me. Judging by the number of people who leave the highway, gas up, then drive slowly towards the palm formations, I’m not the only one who’s fascinated.

For more information on Desert Center see: Wikipedia / The Center for Land Use Interpretation.

For more information on the large series this images are a part of see: James SOE NYUN: Blue Daylight Project.

When he was doing these photocollages, the story goes that Hockney dropped off his film at the neighborhood quickie photo place. In this photocollage you can see the mismatched printing the place did, particularly obvious in the central sand area. After Hockney made the originals, these collages were then editioned, using Hockney’s negatives. The people making the edition tried to replicate Hockney’s originals, which in this case meant going through the headaches of doing an intentionally “bad” job of printing the negatives, trying to match the job the local photo place did for Hockney.

When he was doing these photocollages, the story goes that Hockney dropped off his film at the neighborhood quickie photo place. In this photocollage you can see the mismatched printing the place did, particularly obvious in the central sand area. After Hockney made the originals, these collages were then editioned, using Hockney’s negatives. The people making the edition tried to replicate Hockney’s originals, which in this case meant going through the headaches of doing an intentionally “bad” job of printing the negatives, trying to match the job the local photo place did for Hockney.

large/05baretrees.gif)

large/13espalier.jpg)

%20large/03gettycactus.jpg)