All over town here in San Diego you see the black mustard plant, Brassica nigra, now approaching the end of its blooming period.

The undulating yellow mounds of it doing its thing are a spectacular sight, so much so that Napa Valley, up north in the wine country, has an annual Mustard Festival that’s just come to its conclusion. The festival host the expected Napa wine and food offerings, and also hosts contests in photography, art and cooking with mustard. In addition to how the plant looks, it has an interesting history, as told by Napa pioneer Calvin Chesterfield Griffith, quoted on the Mustard Festival’s site:

This is the story of our early California when it was only a wilderness, with great quantities of trees, beautiful plains, all kinds of wild animals and birds; many, many Indians, and no white men at all.

Father Serra had come from Spain to Mexico to spread the religion of Jesus Christ, and hearing about this beautiful, vast country to the north, decided to explore it. With a few faithful followers and Indian guides, he traveled north through what is now our glorious and loved California. As he traveled he scattered to the right, and to the left, the mustard seeds which he had brought with him from Spain.

The following year, as they returned south they followed ‘a ribbon of gold;’ and following that path again Father Serra established his ‘Rosary of Missions,’ beginning in San Diego and ending in Sonoma.

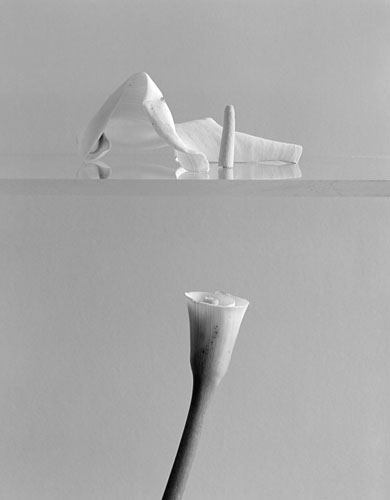

It’s an appealing, romantic story, but it also sidesteps the fact that the mustard has invaded much of the West, and can be found in most of the United States. As a robust winter annual, it can out-compete most native plants, particularly in disturbed locations, and form virtual monocultures that prevent other plants from getting a foothold. The pictures above were taken a few blocks from my house, in Tecolote Canyon. Because of abundant moisture earlier in the year, the plants were well over my head in spots, easily seven feet tall.

To the left is a picture of a part of the canyon where the mustard hasn’t taken over. It’s a good example of coastal sage scrub, rich in plantlife and alive with birds and insects. The white-flowering plant in the foreground is black sage, Salvia mellifera, blooming up a storm, with yellow deerweed (Lotus scoparius) behind it. So what would I prefer–a rich ecological mix of plants that host a range of animal life, or a showy burst of color that nourishes almost no animal life and is about to dry out to a wildfire magnet?

To the left is a picture of a part of the canyon where the mustard hasn’t taken over. It’s a good example of coastal sage scrub, rich in plantlife and alive with birds and insects. The white-flowering plant in the foreground is black sage, Salvia mellifera, blooming up a storm, with yellow deerweed (Lotus scoparius) behind it. So what would I prefer–a rich ecological mix of plants that host a range of animal life, or a showy burst of color that nourishes almost no animal life and is about to dry out to a wildfire magnet?

Alert on a new invasive: Cousin Jenny, a new Master Gardener in South Carolina, alerted me to a new invasive plant, cogongrass, a plant that’s being listed as a treat even worse than the suffocating kudzu. Here’s a link to a story in the Beaufort Gazzette. Like the black mustard, it’s an attractive plant, but it’s also serious bad news.

More on weeds and invasives: I’ve been leafing through Weeds of California and Other Western States, by Joseph M. DiTomaso and Evelyn A. Healy. It’s a sumptuous two-volume set, a coffee-table book of weeds if there ever was one, with 3000 images of the 750 evil species it lists. It also comes with a CD-ROM of the images in the book that can be used without royalties for educational purposes.

In addition to the 750 nasties, there’s a table in the back with potential future threats from plants that are just entering the ecosystem. The book leans towards the technical side, but there’s a handy glossary and index. It took me 20 minutes to figure out that the annoying grass coming up in spots around the yard was tall veldgrass. But with other species I was able to go right to the offender.

I found it striking that a huge number of the weeds–like the black mustard–were of European origin, likely brought over by settlers from there over the past centuries. Controls have since been erected that help reduce the entry into the country of plants that might prove invasive. However, with people, products and produce jetting all around the world these days, it’s inevitable that there will be waves of invading plants from regions other than Europe. The cogongrass that’s of concern in the South, for instance, comes from Asia.

As I wander around the yard inventorying the plants coming up in the crevices, it’s weirdly comforting to know that my yard is contributing to preserving the earth’s biological diversity–though unfortunately I’m not necessarily helping along the species that really need it the most!