Yesterday’s big garden task was to take out a big bird of paradise that we’d planted twenty years ago.

Left: The “before”…

…and the “after”…

The plant had some good things to recommend it: big splashy flowers (if you’re into that sort of thing), a robust plant that needs minimal maintenance, and a requirement for no additional watering beyond what it gets from rainfall here near the coast.

But one bad trait that you don’t often see discussed is that over time the roots can do damage to nearby hardscape. Ours had lifted the brick patio nearby by over an inch over just the past year.

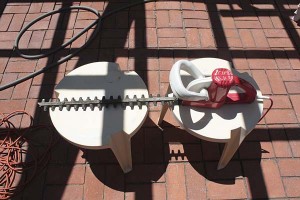

John’s first inspiration was to use the hedge trimmers. The idea was that they’d make quick work of the bird, cutting through the lower stalks as if they were butter, and we’d be done in a couple minutes. They sort of worked, but had a hard time cutting through the fibrous stalks. It might take an hour, not two minutes.

Since it was such slow going I decided that doing things manually, with the trusty hand pruners, would work at least as well and not introduce the issue of losing a finger or two to the blades.

The local landfill has a program where they’ll accept greens waste without charge, chop it to bits, process it into mulch or compost, and sell it for next to nothing. But certain fibrous plant waste is exempted: things like palms, bananas, bamboo and a few other plants…including bird of paradise. So, anything on the list of forbiddens has to be dumped as regular urban waste.

I’m not up on dump fees around the country, but our little expedition cost $34, about the same as a trip to the zoo ($35 per adult) and a deal compared to a day at Sea World ($55-65). And with no food stands selling deep-fried munchies, it was probably a lot less fattening.

While at the dump, it was a chance to see some of the rare local riparian habitat whizz by the window at 35 mph…

…and some blooming buckwheats. It’s not quite a native plant garden, but the edges of the landfill shield some protected and uncommon species.

In fact, immediately to the east, is Miramar Mounds National Natural Landmark, a piece of land designated to be of special interest in a program administered by the National Park Service. The Landmark comes to life during the winter rains, with vernal pools suddenly dotting mesa tops. The federally endangered San Diego mesa mint breaks into bloom, and the ground around the pools comes alive with toads the size of your thumbnail and Pacific chorus frogs…or so I’ve heard. Although I’ve visited vernal pools before, I’ve never made it to Miramar Mounds proper. Bounded by freeways, the dump, and part of the adjacent military base, access is restricted. It’s definitely on my list of places in town I’d love to visit.