I love a good book that surprises you.

When I was talking to a botanist a couple months ago and she recommended Oscar F. Clarke’s Flora of the Santa Ana River and Environs : with references to world botany, I was expecting the book to be a nicely assembled writeup of a watershed a couple of hours to the north.  As such it’d be a good writeup of species I’m using to seeing in my area seen through the filter of someone working in the Los Angeles/Orange/Riverside County region of Southern California.

As such it’d be a good writeup of species I’m using to seeing in my area seen through the filter of someone working in the Los Angeles/Orange/Riverside County region of Southern California.

The volume, which the back cover says “represents a culmination of a lifetime of natural history study,” lives up to my expectation of being a useful guide for studying the plants of the area. But in addition it ends up being full of all sorts of interesting little details that breath life into what might otherwise be an inert textbook. It’s a rich book, not a dense one.

(Edit, July 13, 2010: In addition to Clarke, the book has three co-authors who should be named: Danielle Svehla, Greg Ballmer and Arlee Montalvo. Thanks to all of you for such a great book.)

For example, take some of the details in the writeup on our state flower, the California poppy. Last year I decided that I’d replace my plantings of the typical garden-orange strain with the lower-growing yellow strain that you find locally. The first season’s plants germinated and grew well. This year I was fully expecting the plants to return in profusion, coming up both from last season’s roots and the seeds that the plants dropped. Instead, most of this year’s crop were the big orange garden strain. What went wrong?

Clarke’s description of the species concludes with a sentence that helped answer my question: “Local native populations produce seeds that remain dormant until exposed to winter/spring conditions in combination with smoke or other unknown factors, while populations from central California and commercial cultivars produce non-dormant seeds.” While it didn’t explain what I need to do to get these plants to naturalize, it at least explained that I was battling against some unknown biological forces. I felt better in my failure.

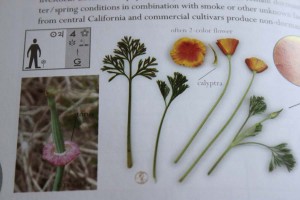

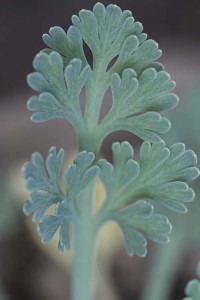

The illustrations in many manuals can be pretty poor, but that’s not the case here. All throughout the book brims with illustrations. Here are some of them from the poppy description. You’ll find closeups of diagnostic plant features, usually with the graphic of a penny for size comparison’s sake. And often you’ll see shots of entire plants. Each writeup also has a little rectangle with a graphic of a human standing next to the plant being described. The idea is that the box will tell you a lot of details at a glances–stuff like size, growth habit, structure of the flower, number of petals, the position of the ovary, and whether the plant is an annual or lives longer. After having stared at the graphics for a couple weeks I still find it a tad confusing, but if you’re good at decoding images instead of reading about the details, this might be just the thing for you. Another minor grouse is that typeface is almost too small for aging eyes like mine. Of course a bigger type would probably result in a larger, less field-friendly manual. But those are minor quibbles.

Back to some plant trivia: About California sea lavender, Limonium californicum, shown here getting ready to bloom, Clarke observes that “The only native California member of this genus, [it] occurs primarily along the immediate coast. It is salt-tolerant (halophytic) and excretes salt on its broad, leathery leaves.” This detail is important to me as I decide which plants to target with the leftover water I’ve gathered from showering. Instead of tossing the soapy, shampoo-spiked water, I’ve been trying to figure which plants wouldn’t mind standing in the second-hand liquids. This species seemed happy enough with the water last year, and the writeup gives me extra confidence that I’m probably not doing it any harm.

(Edit, November 20, 2014: It was pointed out to me that the plant I purchased and depicted here as L. californicum is in reality the INVASIVE L. ramosissimum ssp. provinciale. Apparently even the reputable native nurseries get things wrong every now and then. I will be replacing this plant with something more responsible.)

Life in the Santa Ana River Basin these days is as much about invasive plants as it is native species. Accordingly the book has a number of exotics mixed into the 900 species it describes.

Telling grasses apart can be one of the more difficult things to do in the field. The detailed descriptions and photos help ease that chore. Here are the illustrations for panic veldgrass, Ehrharta erecta, a really bothersome weed in many gardens, mine included.

The weed descriptions, like those for the other plants, have little trivia bits woven through them. About panic veldtgrass you learn that “Livestock find it highly palatable, especially chickens and rabbits.” That sentence might not mean a lot to you, but it explained something I’ve been noticing.

Scooter, the cat, always shows a lot of interest when I’m in the garden, and is most helpful when I’m in the middle of pulling up weeds. And of all the weeds, this is the one that the cat really goes crazy over, often nudging, clawing, fighting you to get to munch on a few blades of the stuff.

Ah, yes, it all suddenly makes sense now: “livestock,” “highly palatable.” Eureka! So to Clarke’s list of chickens and rabbits we can add another species: cats.

So yes, this is a book with lots of information about plants of the Santa Ana region. But it ended up telling me as much about what’s going on in my garden. Very cool.